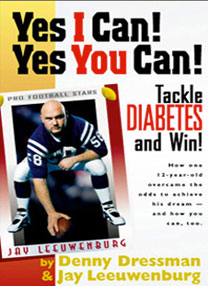

Yes I Can! Yes You Can!

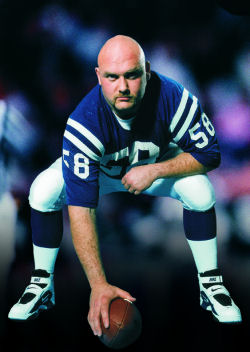

Jay Leeuwenburg started more than 120 games and lined up against eventual Hall of Famers Reggie White and Lawrence Taylor and many other fearsome opponents during a nine-year career in the National Football League.

But first he met Type 1 diabetes head-on.

Purchase BookJay Leeuwenburg started more than 120 games and lined up against eventual Hall of Famers Reggie White and Lawrence Taylor and many other fearsome opponents during a nine-year career in the National Football League.

But first he met Type 1 diabetes head-on.

Diagnosed just days after his 12th birthday, Jay quickly accepted responsibility for managing his disease. Testing his parents' patience and his doctors' knowledge, Jay pushed ahead with every imaginable athletic and competitive interest.

"Not participating would have been like saying, 'Don't breathe,' " he says.

What readers are saying:

"As I am getting further into the book, I'm just amazed at the issues and questions it answers, almost like you were reading my mind!" "Thank you so much for this book. It is a God-send." "I just finished reading your book. It's a keeper!" "I work with newly diagnosed pedi diabetics. I have quotes from the book on my office door that change weekly."He almost lost a foot to infection his senior year in high school, but persevered to become a first-team all-state football player and a qualifier for the state wrestling tournament - in his first and only attempt at the sport. He then played on the greatest teams in the history of University of Colorado football, and became a unanimous All-American center.

Despite his collegiate strdom, National Football League teams passed on him until the 9th round of the 1992 college draft. "My goal immediately became to play the number of years in the NFL for the round in which I was drafted," he says.

Overcoming the ignorance about diabetes that he found throughout pro football, Jay not only accomplished his goal but also started at every interior line position, a distinction few NFL linemen share. Through it all he learned so much about his disease that he became, in his doctor's coined description, a "diabetologist."

Bothered by the absence of diabetic athletes as positive examples during his own childhood, Jay decided that his stardom presented both an opportunity and a responsibility: to become a role model for other diabetics, especially children.

Jay's determined refusal to let Type 1 diabetes prevent him from living life to the fullest is an example anyone can follow. His message: "Yes You Can!!" applies to everyone learning to live with diabetes, regardless of age - including the parents of children with diabetes.

Ask Jay Leeuwenburg if a person with diabetes can enjoy life as completely as anyone without it, and he'll answer, "Yes I Can! Yes You Can!!"

'Highly Recommended'

"Jay's experiences and attitude can help anyone who is struggling with a new diagnosis or who is overwhelmed with caring for themselves. His experience is about persevering in the face of the challenge of diabetes and never letting it be an excuse. That's a great story for everyone."Children with Diabetes

Read Full Review

Being diagnosed with diabetes requires a new way of thinking. You learn about insulin, checking blood sugars, carbs, exercise -and the importance of planning. But you don't give up your dreams, and you don't take "No" for an answer. That's the message of Yes I Can! Yes You Can!, a book about Jay Leeuwenburg, who was diagnosed at age 12 and went on to play nine years in the NFL as an offensive lineman. Written by Denny Dressman and Jay, the book alternates between Denny putting everything into perspective and Jay sharing his personal experiences, such as:

I knew from just the mere fact of going to my normal three-month doctor visits that there were thousands upon thousands of children who were seeking answers to what I thought were just basic questions about living with and managing diabetes. And they were getting such outrageous advice that I couldn't understand.Jay's experiences and attitude can help anyone who is struggling with a new diagnosis or who is overwhelmed with caring for themselves. His experience is about persevering in the face of the challenge of diabetes and never letting it be an excuse. That's a great story for everyone.For instance, 'You can't be a cheerleader. You can't play soccer.' The message was, you can't do these things because you're diabetic. I thought it would be an injustice not to use my career and that instant celebrity as a forum. So pretty early on I made a commitment that I would send the message to youngsters that, 'You know what, you can do anything you want.'

Highly Recommended

-- JSH'Valuable advice'

"The word 'victim' was never in Jay's vocabulary. When he set his mind to do something - riding a pogo stick for blocks, bicycling for miles or playing sports - he did it. Dressman and Leeuwenburg provide encouragement, hope and valuable advice for families dealing with a potentially debilitating disease. Their motivating message emphasizes that it can be managed, controlled and conquered."The Bonham Group

Read Full Review

Review in Boardroom Sports

by Don Hinchey of The Bonham Group:

Boardroom Sports hasn't been shy about calling attention to the dark side of sports - athletes behaving badly. That's why it's so refreshing to highlight an athlete whose actions are a credit to himself and a positive example for others.

Such an example is neatly chronicled in Yes I Can! Yes You Can! Tackle Diabetes and Win! (ComServ Books) by Rocky Mountain News Associate Managing Editor Denny Dressman and former Colorado football star Jay Leeuwenburg. It's the inspirational story of Leeuwenburg's refusal to let diabetes prevent him from fulfilling his athletic dreams and a vigorous affirmation that people with diabetes can lead successful lives.

Jay was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes a few days after his 12th birthday. Initially, the news created parental confusion, concern and even guilt. After the shock wore off, Jay's folks responded strategically. They sought expert medical help and found it in the form of Dr. Pat Wolff, a prominent St. Louis endocrinologist with an uncompromising approach: make the child responsible for the problem and give him or her the tools to deal with it. As she told Jay: "It's up to you. You're smart, and you get this. We need to make a plan."

Wolff found a receptive patient in Jay. The word victim was never in his vocabulary. When he set his mind to do something - riding a pogo stick for blocks, bicycling for miles or playing sports - he did it. He sums up his attitude at that time with a sijmple phrase. "To not participate," hs says, "would be like saying, 'Don't breathe.' "

Jay did not play football until he entered Kirkwood High School in St. Louis, where he starred in football and wrestling. While there, Jay's journey with his disease was one of self-education, educating others about his particular needs (especially coaches and trainers) and, most of all, managing his diabetes regimen.

Because of his athletic prowess at Kirkwood, Jay was pursued by several major college football teams including Notre Dame, Iowa and Missouri. But it was the University of Colorado who expressed the most interest, luring him to Boulder in 1987.

While at CU, Leeuwenburg played for Bill McCartney in four bowl games, including back-to-back national championship Orange Bowl games, both against his former suitor Notre Dame. The buffaloes split those match-ups with the Irish, but they were prime time opportunities for Jay to showcase his talent. His senior year, Jay was team captain and a unanimous All-American selection at center. After Jay's senior season, he was not drafted until the ninth round by the Kansas City Chiefs. Clearly, some teams had reservations about diabetes. He was in Kansas City just long enough to be acquired by the Chicago Bears, where he played against future Hall of Famers Lawrence Taylor and Reggie White and had a memorable sideline encounter with the immortal Walter Payton.

In Chicago Jay was a community favorite and made many good friends. Among them were the folks from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, who recognized Jay's popularity and parlayed it into speaking engagements on behalf of the JDRF. This popularity and usefulness blossomed after the Colts signed Jay as a free agent. While in Indianapolis, Jay and his wife Ingher established Jay's Corner, a section of the RCA Dome where their generosity allowed 150 diabetic kids and their families to enjoy each Colts home game. After games, Jay would often interact with these people and communicate how to manage the disease.

Communication is still a Leeuwenburg strength.

Today, Jay teaches at Colorado Academy and appears regularly as a Broncos and college football analyst on FSN Rocky Mountain and other television networks.

He also counsels corporate executives on how to help their employees control the explosion of Type 2 diabetes in their workforce and increase their knowledge of Type 1 diabetes so they don't underestimate workers who have it.

The Bonham line: Dressman and Leeuwenburg provide encouragement, hope and valuable advice for families dealing with a potentially debilitating disease. Their motivating message emphasizes that it can be managed, controlled and conquered.

'An important story'

"This book is not only well written and interesting to read, but it also tells an important story. The word 'inspiring' gets thrown around quite a lot, but I can think of no better word to describe Leeuwenburg's experience with diabetes. His dedication is remarkable, and his accomplishments show it."Writer's Digest

'Most inspirational'

"I couldn't put it down. I read the whole thing before the "Friends For Life" conference was over and thoroughly enjoyed it. It's one of the best sports books I've ever read - and certainly the most inspirational."Lance Porter, Editor

Diabetes Positive Magazine

'Real-life examples'

"For the diabetic, Yes I Can! Yes You Can! is a series of real-life examples of dealing with the disease. For the non-diabetic, it's an education about what diabetic athletes - and diabetics in general - must go through almost every hour of every day."Ralph Loos

The Southern Illinoisan

Read Full Review

Review by Ralph Loos of The Southern Illinoisan:

For the diabetic, "Yes I Can! Yes You Can!" is a series of real-life examples of dealing with the disease. For the non-diabetic, it's an education about what diabetic athletes - and diabetics in general - must go through almost every hour of every day.

Dressman provides the overall footing and storytelling for the book, while Leeuwenburg pops in from time to time to provide details.

About his diagnosis and athletics, Leeuwenburg writes, "Minus anything else happening to me, I refused to not be able to participate. I had to be able to play any sport I wanted. I needed that physical outlet.

"They said I would be able to, but I'd have to make some modifications."

It's those modifications - detailed throughout the book - that will make readers with diabetes, or those close to someone with diabetes, chuckle, nod, sigh and perhaps even cry.

Besides being entertaining, the book is a warning to young and old: Diabetes is a serious disease.

It inspires, telling tales of Leeuwenburg's life as a diabetic. Above all, it motivates.

For Atheletes

Jay's endocrinologist, Dr. Patricia Wolff, coined the word "diabet-ologist" to describe the level of knowledge and understanding he acquired to ensure that diabetes would not interfere with his participation in athletics or endanger his well-being.

Dr. Wolff's "diabet-ologist" offers these Word of Wisdom for anyone managing diabetes and playing sports, whether competitively or recreationally.

1. EducateEducate yourself to the signs and symptoms of insulin reactions. Know the first signs and each progressive sign as they change your body and thoughts. Educate yourself to know how long you have before you get into the danger zone of non-compliant behavior or confusion.

2. Anticipate

Know the activity you are engaged in, and know when the problems may arise before they occur. If you are planning a two-hour run, know that the last 30 minutes are the time when lows could become a problem and be prepared to deal with them. If a certain time of day is difficult for you, plan your insulin accordingly. On game days I would cut my insulin demands in half!

3. Hydrate

Dehydration can not only lead to physical problems but also result in false blood glucose readers of higher numbers. When diabetics have high blood sugars the body flushes the extra sugar out of your body through the kidneys, and that uses fluids from your body and dehydrates you. Dehydration can often be misunderstood as high blood sugars (the symptoms of dehydration and extreme high blood sugars are very similar), aches and an overall malaise.

4. Use Restraint

Don't overreact. A blood sugar of 200 is just fine. It is much safer to have slightly elevated sugars than to constantly fight lows throughout the activity. As long as your blood sugars do not stay elevated for extended periods of time, you are not in danger of causing serious long-term problems. It is much more threatening to have extreme lows while exercising than moderate highs.

Check with your physician before you administer insulin during competition. And remember that insulin is used much more efficiently during exercise, so it will not take as much insulin to lower your high readings. My insulin needs changed from a non-exercise dose of 1 unit lowering my blood sugars 20 points, to a dose of 1 unit taken during exercise lowering my sugars 50 points! That's a huge difference, so KNOW YOUR BODY!

5. Communicate

Tell someone else what is gong on. Tell a coach, a trainer or a teammate that you need to treat your sugar low. If you ever get in a situation when you drop into a dangerous low blood sugar situation, those precious seconds can make the difference between a scare and a trip to the hospital. Don't keep it a secret! There were plenty of times during a game when I would make a mistake and teammates would joke, "Do you need to eat?" Sometimes I did, and the reminder helped me out.

6. Don't Hesitate

Always have some kind of high-energy food available, and take time out to eat to treat your low blood sugar. When I played sports I was able to tell the signs of a low blood sugar coming on so I did not have to miss plays but instead could wait until a timeout to treat my low. Having said that, it was paramount that the food I had would get into my blood stream fast. I would either have a regular soda or fruit juice on the sidelines or nearby. I even kept Lifesavers in all my teachers' desk drawers. In my regular life outside of football I use Skittles because they don't freeze in the winter and they don't melt in the summer. It does not matter the brand of the food, just that it is a simple sugar that can be digested very quickly so it enters your blood stream fast. During exercise it is important to err on the side of being high rather than low. If in doubt eat first and check later.

For Coaches and Teachers

The most frequent comment parents make is, "Tell the coach (or teacher) not to hold my child back just because he/she has diabetes. Let them participate."

Diabetes doesn't have to limit a child's activities or sports participation. It doesn't have to limit their ability to perform as well as any other child in class or on the field or court. The key, as much for every teacher or coach as for every child, is knowledge.

These tips, from one of those diabetic kids - one who grew up to become a college football All-American, a National Football League star, and eventually a third grade teacher — should help:

1. Know who your diabetics are.Don't wait until the diabetic student in your classroom, or diabetic athlete on your team, is having a low blood sugar to find out they are diabetic. It's okay to ask students at the beginning of the school year, or at the start of a season's practices, if anyone has a medical condition that you should be aware of. Let them know you want to know so you can help them make sure it is never a problem for them.

2. Have a plan for lows.

In the classroom, decide on a plan before your student has a low. Decide if it is okay to eat in the classroom. If not, where can they eat? Don't have the diabetic student go alone when they are low. Send a friend with them if they will be out of sight. Make them check their sugar levels, particularly if they have difficulty identifying a low. On the field or court, know what food you will have available, where it will be kept, and how it will be dispensed.

3. Don't eat the food!

Emergency food is Off Limits to everyone, including diabetic students or athletes - unless they are low. Teachers, coaches, fellow students and teammates are notorious for eating the emergency food that has been set aside for lows. Treat the food as medicine. Don't let the student/athlete eat at will. Monitor them to make sure they are low.

4. Check and replenish supplies.

You will be amazed how quickly the food disappears. Be sure to restock before you run out completely.

5. Know the signs of hypoglycemia.

They change and are different for each diabetic and for each athlete. Just because you may have taught or coached a diabetic in the past, don't think they are all the same.

6. Have a plan for treating high sugars.

Know or find out if your diabetic student or athlete gives their own shots. Do they bolus? Remember, you are not the doctor. But at times children need extra insulin. If a diabetic is high, the No. 1 thing is to drink water! Dehydration is the first problem. Drinking water helps fight ketones and helps the kidneys. Remind your diabetic, if they normally bolus for highs, use about one-half.

7. Make the student/athlete part of the process.

It is not up to the teacher or coach to manage their student's or athlete's diabetes. It is the diabetic's responsibility to identify lows. The teacher or coach is the diabetic's support. Watch for signs. If you notice patterns, help them see them. Are they always low during tests? Help them plan for that. Before they go to phys ed, ask them if they have checked their sugar.

8. Don't try to be the doctor.

As a teacher or coach, you don't know all there is to know about diabetes, and you are not expected to know everything. It is okay to say, "ask your doctor. I don't know." It is better to seek information than to give bad dicrection. Children know if you try to pull the wool over their eyes. Don't lose that trust. It isn't worth it.

9. Communication is key.

Talk about what you see. Communicate with parents and diabetics about patterns and concerns, what they do well and what they need help with.

10. Teach/coach them on their diabetes.

The lesson is simple and straightforward, in both school and in life: If you want good grades, take care of your diabetes. If you want to play better, take care of your diabetes. If you want to enjoy life and participate fully, take care of your diabetes.

For Parents

In chapter 14 of Yes I Can! Yes You Can! Ingher Leeuwenburg, Jay's wife, sums up the anxiety and fears that many parents feel as they try to help their diabetic children learn to live successfully with their disease.

"There are a lot of parents of children with diabetes who are looking for that miracle," she says. "Jay's message is not professing a miracle. It is out there communicating how to deal with challenges in your life. It is not giving false hopoe. It is not sayingthere is an easy way out.

"It is saying, 'If you put the effort in, if you're committed, if you're educated, if you take the necessary steps, you will succeed."

If you're the parent of a child with diabetes, see if these tips from Jay help you respond more confidently to the challenges you and your child encounter in your daily lives:

1. Create a diabetic family.Encourage everyone in your family to accept diabetes as a part of everyday life. For example, avoid having two menus in your home, one for the diabetic child and another for everyone else. Instead, have your family eat the same meals. No one will go hungry, and you may all start to eat a healthier diet. Don't have different rules for your diabetic child than you have for your other children. If your diabetic child wants to have a sleepover, support it - just as you would if your non-diabetic child had come to you. You need to set guidelines you are comfortable with, but don't instantly say, No! Use the activity as an opportunity for your child to learn how to manage diabetes and enjoy life. It's a good idea to make sure the supervising adult is aware that your child needs to take insulin and test blood sugar levels, but put responsibility for self-sufficiency with your child.

2. Have a schedule!

You don't have to have everything at the same time every day, but meals especially help if they are at a consistent time. This is not to say you can't go out or do something different. But a different meal time every day makes it much more challenging to manage insulin levels.

3. Always have emergency food handy.

As an adult, never forget to have some fast-acting food ready for your child in case he or she is having a low blood sugar. You don't have to make every low a learning experience or a lesson in responsibility. Have your diabetic try to be responsible for their own health, but you are the adult; make it part of your planning.

4. Don't overreact, especially to high sugars.

Use blood tests as a tool, not to "catch" your diabetic child sneaking extra food. If your child has a high sugar for three days in a row at the same time of day, think about changing insulin needs. Be sure to coordinate with your doctor or dietician before you make a change.

5. Slowly give your child more responsibility.

Depending on your child's age and their maturity level, start making them aware and responsible for their own care. It may be giving their own shots. Figure out how much to blous for a meal. Count carbs. Pack their own meals. Remember that, at some point, they will leave home and be on their own. Your goal is to help prepare them to be safe and in control of their diabetes. Some of the best words of advice my parents and I received was, "No matter how much your parents want to have this disease for you, they can't. You, as a diabetic, ultimately are the only one who can control and effect your own health."

6. Let your child make mistakes, and help them learn from them.

Talk to your diabetic child about the choices they make and how those choices affect their body. If they have to have that triple-decker ice cream sundae with hot fudge, then don't ignore the extra insulin needed when they come home and their blood sugar is 400 and they throw up. Discuss how having that pizza at Suzie's house with regular Coke wasn't the best idea, and how water would have helped so much more. Or at least tell them to take extra insulin and take it when they go to the bathroom, which they surely had to do anyway!

7. Don't treat your diabetic child differently.

If your diabetic child is out of line, call them on it. If they do a good job, praise them. But don't give extra praise just because the child has diabetes. Never say, "Wow, Johnny got a hit; isn't that great because he has diabetes!" It's great because it was his first hit - diabetes had nothing to do with it. Don't let diabetes be an excuse, either. Never say, "Oh, it's okay to steal because she has diabetes." Wrong is never okay.

8. Puberty is hard for diabetics, too.

Hormones affect blood sugars. Know that your teenage diabetic child will rebel and be angry. Have the foundation in place to talk with your child about diabetes and anything else that comes up. High school was the most difficult time for me and for many other diabetics.

9. When traveling, always keep medication in your carry-on.

Have a supply of insulin and syringes or pump site kits in your unchecked luggage. It might sound obvious, but you wouldn't believe how many people pack these vital things, only to lose their luggage or have a flight change and be separated from their bags -and their medicine! The last thing you want to do on vacation is to have to get a prescription and find a drug store to buy insulin and syringes. I have never had anyone in airport security deny me or stop me because of my supplies. But you should have a prescription from your doctor handy to explain the need, just in case.

10. Teach your child to become educated about diabetes and the human body.

So much research and knowledge is being generated everyday about diabetes that it is hard to keep up. But every diabetic needs to try. Diabetes management is constantly changing and improving. Your child's needs will change; their body will change; and so will their daily regimen. Encourage them to be flexible as they grow, and do what works. There is no one right way, or one right answer. We all hope for a cure, but until one is discovered, there is no reason why your child can't use what is available to be healthy and productive.

Name: Jay Leeuwenburg

College: University of Colorado

Degree: B.A., English

College Football Distinctions: Unanimous All-American, 1991

Three-year starter at center

Appeared in four bowl games

Starred on 1989 National Champion Team

NFL Career: 9 seasons (1992-2000)

NFL Teams: Chicago, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Washington

Position: Offensive line

Pro Football Distinctions: Pro Bowl alternate; played in 4 playoff games

Profession After Football: Third Grade Teacher

Jay was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at the age of 12 but went on to become an all-state football player and state tournament wrestler at Kirkwood High School in suburban St. Louis.

He was recruited by many major college football programs, and accepted a scholarship to the University of Colorado. He earned his degree in English, completing his undergraduate course work by the end of his junior year. During his senior season he was enrolled in the Graduate School of Business, and took some education courses.

During Jay's college football career, CU played for the national championship in back-to-back Orange Bowl games, both against Notre Dame. Jay started at center in both games, two of four bowl games in which he played.

The Buffaloes were unbeaten going into the first one, in 1989, but lost. They rallied from a slow start the next season to capture the national title.

In his senior season at CU, Jay was a unanimous All-American, the first-team center on every All-American team named in 1991. He allowed only one quarterback sack his entire senior season.

Jay played nine seasons in the National Football League, including four with the Chicago Bears (1992-95) three with the Indianapolis Colts (1996-98) and one each with the Cincinnati Bengals (1999) and Washington Redskins (2000). He started 129 regular-season games, was a Pro Bowl alternate, and played in four NFL playoff games. He is one of only a few NFL offensive linemen to start games at all five offensive line positions.

Jay never missed a down of football because of any diabetes-related complication.